Every now and then the newspaper archives turn up a real gem, and it’s easy to get diverted from

one’s main search. In this case I was following up the rags-to-riches story of Mary Jane Hopkins

who was rescued from her life in North Shields to live in York with a rich uncle, when I came across

such headlines as: THE FEMALE BRIDEGROOM; A LADY PLUMBER WHO DRESSED AS A MAN; A

WOMAN MARRYING A WOMAN. It wasn’t just me who was intrigued by this Chancery case,

searching further it made headlines all around the English-speaking world, from Los Angeles to

Auckland, and it had all happened in Clapham, with a marriage ceremony in Woodford in Essex.

The main player in this drama was Rachel Elizabeth Cullener; born Rachel Golding on the 11th June

1819, she had married William Henry Smith Cullener on the 28th December 1843, and they had

four children, Henry born on the 28th December 1839, Emma Louisa born on the 18th January

1842, Rachel Elizabeth born on the 18th July 1844 and William born on the 31st July 1850. Rachel

appears on the 1841 census as Rachel Golding, aged 22 living in Clapham with a one year old son

Henry Golding. (His birth was registered in the first quarter of 1840 in Newington as Henry Culliner

Golding, Emma Louisa’s birth was not obviously registered. Rachel Elizabeth’s and William’s births

were both registered in Wandsworth.)

William Henry Smith Cullener’s first wife, Rachel Young, whom he had married in 1819, died in

August 1838, apparently childlessly. WHS himself died early in 1853, and surprisingly his widow

Rachel Elizabeth had all four children baptised at Holy Trinity Church, Clapham on the 2nd

February 1853, the day his will was proved. Did she believe this would prevent her two first-born

children from being legally illegitimate?

In 1851 the Culleners were all happily at home at 4 Apsley Place, Clapham. WHS was a proprietor

of houses and a fundholder; living with them was Elizabeth Young - aged 62 she might be the

sister of his first wife, though she could also be the sister of Rachel Elizabeth’s mother, Charlotte

Young. (Perhaps all these Youngs are related anyway). WHS’s will - written in 1848 and proved on

the 2nd February 1853 - is the subject of the Chancery case that arose in the 1890s, and it is a

closely written, almost undecipherable document that must have been carefully scrutinised by all

the lawyers involved. Basically his wife was the main beneficiary as long as she remained

unmarried, when his children would inherit, and then their legitimate children. He does leave 19

guineas to his “god-daughter Caroline Newland, daughter of James Newland of Havering in the

county of Essex, Parish Clerk”.

The family has moved to 6 Union Road, Clapham by 1861, and now consists of the widowed Rachel

Elizabeth, her son William, daughter Emma Louisa and her husband Frederick Jeremiah Clarke.

Also living with them is a cousin of WHS, a certain Sophia Newland, born in Havering-atte-Bower,

and the daughter of a the village schoolmaster and parish clerk. Rachel’s son Henry had died in

1860, and Rachel Elizabeth junior is living with her [step-] aunt Elizabeth Young not far away at 10

St Andrew’s Terrace. She died in 1868, and this is the entry in the Probate Calendar:

CULLENER

Rachel

Elizabeth.

30th

January.

Letters

of

administration

of

the

Personal

estate

and

effects

of

Rachel

Elizabeth

Cullener

late

of

Campbell-villas

Eastdown

Park

Lewisham

in

the

County

of

Kent

Spinster

deceased

who

died

2

March

1868

at

1

Campbell-villas

aforesaid

were

granted

at

the

Principal

Registry

to

Rachel

Elizabeth

Stanley

(Wife

of

James

Stanley)

of

Sygnet

in

the

County

of

Oxford

the

Mother

and

only

Next

of

Kin

of

the

said

Deceased she having been first sworn. Effects under £100.

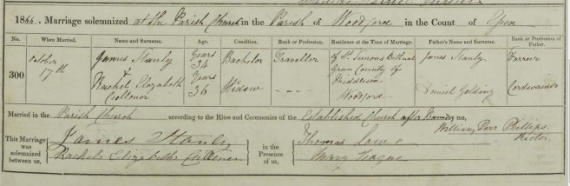

For Rachel Elizabeth senior had married again on the 17th October 1866 in Woodford in Essex; her

new husband was James Stanly, a bachelor aged 34, and a Traveller of St Simon’s Bethnal Green,

County of Middlesex, whose father, also James Stanly, was a Farrier. This entry in the marriage

register was also to be very closely scrutinised in that Chancery case in the 1890s.

Despite her husband having left her comfortably off, by the late 1850s Rachel Elizabeth senior was

in some financial trouble. The main cause of this seems to have been her son-in-law Frederick

Jeremiah Clarke, a timber merchant, and as one of the Australian papers put it: “in an evil hour Mrs

Cullener was induced to become security for him. He failed to meet his liabilities; the creditors turned to

her: and the widow was threatened with ruin”. In 1859 she had appeared at the Court for Relief of

Insolvent Debtors, and at the beginning of 1867 as Rachel Elizabeth Stanly she is in the Debtor’s

Prison.

Rachel had some novel ideas on how to get those creditors off her back.

It

occurred

to

her

that

she

would

be

able

to

elude

pursuit

of

the

creditors

by

passing

as

a

man,

and

she

also

considered

that

she

would

be

better

able

to

earn

her

livelihood

in

that

character.

She

accordingly

about

1865,

first

assumed

male

attire,

[...]

and

she

had

habitually

worn

the

same

up

to

the

present

time,

passing

under

the

name

of

Henry

Neville

Smith,

and

carrying

on

the

business

of

a

plumber

and

paperhanger

under

that

name.

(From a report on the trial in the Yorkshire Evening Post of 2nd December 1893)

It was apparently her daughter Rachel who suggested she get married in order to move her

remaining resources onto her children, and thus further confound the creditors. Her children

would be collecting rents etc. and divvying up the proceeds so she had an income. Although she is

named in several legal documents as Rachel Elizabeth Stanly (and where is Sygnet in Oxfordshire?)

she doesn’t appear thus in any census; but with the benefit of hindsight - and that case in

Chancery - she can be found, in the 1871 and 1881 censuses as Henry Neville Smith, house

decorator and paper hanger, living first in Deptford and then in Bermondsey, and accompanied by

her wife Sophia!

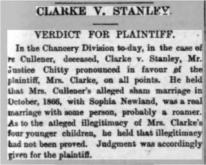

The Chancery case begun in 1891 (in re Cullener deceased (Clarke v. Stanly)) hinged on the validity

of her marriage in 1866, the rights of the beneficiaries of WHS’s will from 1853, and also the

legitimacy of some of her daughter Emma Louisa’s children. For it turned out now that Rachel

Elizabeth was claiming that the marriage had been a sham, that she had played the part of the

groom and Sophia Newland had taken her part as bride - they had already been living together as

Mr & Mrs Smith for over a year. The judge refused to believe this as he had a bit of paper - the

marriage certificate naming James Stanly as the groom - that said it was a valid marriage.

Unfortunately the vicar who performed the ceremony, and the two witnesses, both parish officers,

were all now dead. The signatures were carefully scrutinised and declared genuine, though the

two women claimed to have practised them beforehand. Looking at the entry in the register with

more cynical eyes, to me it does look suspicious. The groom, a traveller and declared a random

passer-by by the judge, can sign his name, and there is far too much detail given in his present

residence.

Click to enlarge

“Dressed in ordinary widow’s clothes, she gave her evidence in a masculine voice” as the papers

were quick to comment. Rachel Elizabeth Cullener used her original name (thereby surely

disputing the Stanly marriage?) and gender, during the Chancery hearings. But what never

appears to be explained is why Rachel now chooses to declare, under oath, that her marriage to

James Stanly was a sham, when she didn’t need to, though this would of course be denying her

children their inheritance, as she was strictly speaking still the widow of WHS.

Anyway Rachel and Sophia continued to live together as husband and wife, and stayed together

until about 1885, when apparently as business declined and money became short, they separated.

In 1891 Henry Neville Smith, now a “widower”, but still a paperhanger, is living at 31A Queens

Road, Peckham, with “cousins” Rachel Agnes and Henry Cullener, the children of Rachel’s son

William from his first marriage. Rachel - as Neville Henry Smith - appears at this address on the

1892 Peckham voters list. Sophia in 1891 is back home in Havering-atte-Bower, single with the

surname Newland and “living on means”, in 1901, aged 72 and single, she is an inmate in the

Romford Union Workhouse and Infirmary, aka Oldchurch Hospital. She died there the following

year. Now I don’t know what Rachel and Sophia’s relationship actually was, but the judge hinted at

his disapproval when he referred to Sophia as Rachel’s “creature”.

Rachel, who was born in 1819, is rather cavalier with her age after WHS’s death. She says she’s 36

on her marriage to James Stanly in 1866; she’s 46 in 1871, 47 in 1881 and 51 in 1891. Her death

was registered In the Camberwell district in 1898 with the name Rachel Elizabeth Cullener, when

her age is given more or less correctly as 77.

The other part of the case concerned the legitimacy of Emma Louisa Clarke’s seven children*,

particularly those four born after the disappearance of her husband, the bankrupted Frederick

Jeremiah Clarke, and was brought against her mother by Emma Louisa’s oldest daughter Rachel

Elizabeth Molz (née Clarke). Obviously worried about her own inheritance, she even gave evidence

of having caught her mother in flagrante with another man. The judge ruled however that there

was not sufficient evidence of Frederick’s absolute disappearance, that he could easily have had

“access”, and that, for all the law knew, the other children were as much his as the eldest daughter.

Perhaps it says something that Emma had her two youngest children baptised on the 30th January

1889 at St Mary’s Walthamstow, when they were 14 and 9 years old respectively, citing Frederick

Clarke as their father.

*The fact that Emma Louisa was legally illegitimate herself was never brought up, WHS’s son

William Cullener was the only surviving legal beneficiary and trustee of his father’s estate (though

as the will was written in 1848, two years before he was born, he isn’t mentioned in it). William

appears to have kept a rather low profile during these proceedings, and his own personal

relationships seem somewhat clouded! However the family must have known all of this, even my

own family who had nothing to inherit, remembered that my grandfather had been born before

his parents’ marriage and could not benefit from any (imagined) inheritance; “poor old uncle

Frank”.

Tales around the tree

Culleners, Chancery and cross-dressing - “a plot worthy of a dime novel” (Los

Angeles Herald, 21 May 1894)

Click to enlarge

Lincolnshire Echo 16 December

1893